What if I told you the most affordable homes in New Castle County generate 10 times more tax revenue per square foot than the large-lot suburban development we keep approving?

And what if I told you they also cost just one-tenth as much to maintain?

The reality is completely flipped from what we’ve been told. Affordable housing isn’t a burden on the budget. It’s the backbone of our economy. The verdict is overwhelming. Compact, efficient neighborhoods, the kinds often labeled as “affordable housing,” don’t just save money. They are the most fiscally productive parts of our communities. They keep services funded and taxes lower. They outperform every other type of development by a wide margin. They generate more revenue, require less infrastructure, and deliver a much higher return on public investment.

So why do we keep building the opposite? And what is it costing us?

The kinds of development we keep approving are draining public funds. They require more roads, more pipe, and more maintenance, all which ends up pushing our taxes higher year after year.

These homes don’t pay for themselves . They cost the public more than they generate, and we’ve been building more of them than ever.

And yet, despite all that spending, services are still falling behind. Roads deteriorate. Sewer systems age. Firefighters and EMS need more funding to patrol a larger area. Budgets stretch thinner. We are stuck in a cycle where the more we build, the more we lose.

So where is all the money going?

To understand why affordable housing matters so much, we need to look at where our money comes from and where it goes.

In New Castle County, property taxes make up over half of county revenue. Another 12 percent comes from property transfer taxes. The rest includes fees, licenses, and miscellaneous sources. In other words, land is our crop. If we misuse it, the entire system underperforms.

On the expense side, over 40 percent of the county’s operating budget goes toward sewer and road systems. These are services directly tied to how and where we build.

When you step back and look at the full budget, the numbers are staggering.

The county’s FY2026 budget totals more than $455 million, and nearly half of that is tied to infrastructure. Between roads, sewers, stormwater, and the staff it takes to manage them, we’re spending more than $200 million a year to serve our current development pattern.

And the more we sprawl, the more we have to spend, both now and every year into the future.

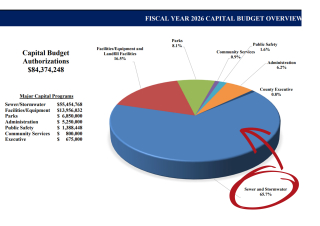

Caption: New Castle County's FY2026 Capital Budget. The largest share, nearly two-thirds, is dedicated to sewer and stormwater infrastructure. These costs scale directly with how far we spread out our development. The farther we build, the more we pay.

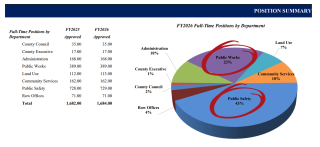

Caption: New Castle County's FY2026 Operating Budget. Two of the largest departments, Public Works and Public Safety, are heavily impacted by how we build. More roads and more spread-out neighborhoods mean more to maintain and patrol, year after year.

Let’s break down the math. Don’t worry, a fifth grader can do it.

Supporting a single-family suburban home requires, on average, 78 feet of infrastructure per household. That includes streets, pipes, utility lines, and more. In compact neighborhoods like rowhomes, townhouses, or small apartments, that number drops to just 8 feet .

Now consider that the annual maintenance cost is about $12.50 per foot:

With an estimated 35,000 suburban-style homes in the county, that translates to:

$875 × 35,000 homes = $30.6 million per year in avoidable infrastructure costs

Meanwhile, in FY2026, New Castle County is spending nearly $88 million on public works. That is nearly a quarter of the total budget. And property tax revenue has remained flat.

It doesn’t take an Alan Turing to realize the math doesn’t add up.

Here’s the twist. The homes we call “affordable” — townhouses, rowhouses, duplexes, small apartments — are not an extra. They are not a moral gesture or something to consider when the budget looks good. They are a smart, proven investment that delivers better returns than any other type of development.

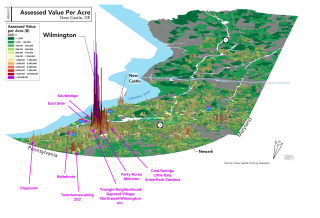

These homes generate more tax revenue per acre and cost less to serve. In neighborhoods like Trolley Square, Forty Acres, the Triangle, Union Park Gardens, and Midtown Brandywine, the data is clear. These compact, walkable communities pay for themselves many times over. They do not drain the budget. They help carry it.

Caption: : The images above show Forty Acres — a compact, walkable neighborhood in Wilmington — from both street level (top left) and aerial view (top right). Developments like these generate up to 10 times more property tax revenue per acre than typical suburban subdivisions like the former Hercules golf course (bottom left) or new construction outside Middletown (bottom right). The difference is in the design. Not just the density, but the efficiency.

Despite the clear financial benefit of compact housing, 85 percent of new development applications are for large-lot single-family detached homes. These homes are the least efficient and least affordable type on the market.

They come with higher costs not just for buyers, but for the public. They require more roads, more pipe, more maintenance. The average annual infrastructure cost is $975 per suburban home, compared to just $100 for a compact home.

And that is just the cost side. The revenue side tells an even more dramatic story.

New Castle County gets more than half its revenue from property taxes. That means land is our crop, and homes are what we grow. But not all homes produce the same return.

Urban3, a national leader in public finance modeling, has shown that compact, walkable neighborhoods in New Castle County generate 10 to 50 times more tax revenue per acre than large-lot suburban development. One block of a walkable neighborhood can outperform an entire big-box retail site.

Caption: Zoom in! This map, adapted from a 2020 Urban3 presentation, illustrates the property tax revenue generated per acre across New Castle County. Neighborhoods have been labeled to help orient viewers to familiar areas and highlight the outsized fiscal contribution of compact, walkable communities.

Meanwhile, suburban homes cost significantly more to maintain. So we are growing the least productive crop and spending the most to keep it alive.

We should be building the homes that generate the highest revenue and cost the least to maintain. That is what affordable housing is. It is smart, high-yield development that keeps the system working.

Delaware is short more than 50,000 housing units, yet we keep building the type of housing that is least affordable and least financially productive.

This mismatch has real consequences. Our population is aging rapidly. From 2010 to 2022, the number of residents over 65 grew by 63 percent, while the number of millennials shrank. Young families, the backbone of a healthy economy, are being priced out.

And when there is nowhere affordable to live, young people leave. Businesses follow. Tax revenue shrinks. Services struggle. The spiral tightens.

Affordable housing is not just about equity or fairness. It is about holding the entire system together.

If compact housing is the most productive, why aren’t we building more of it?

Because we have made it nearly impossible.

Zoning codes ban or restrict the very housing types that built our most successful neighborhoods. Duplexes, small apartments, homes close to the sidewalk, these are illegal in most of the county. The most productive neighborhoods in New Castle County could not be built today under current law.

At the same time, sprawling subdivisions are fast-tracked and subsidized. Developers are not the problem. They are responding to the incentives we have put in place. Right now, those incentives reward the kind of development that costs the most and delivers the least.

We do not need just more housing. We need smarter housing.

That means:

The numbers are simple. The return is massive. And the opportunity is right in front of us.

We’re locking up more than $200 million every year to support a development model that loses money over time. Not because we have to, but because we’ve built the rules around it.

It’s a financial trap.

Suburbs are not the enemy. But the imbalance we have now is unsustainable. We need to be building a healthier mix of housing, where people of all incomes can live and where growth actually benefits the budget.

When we build housing that young families can afford, we grow our workforce. We support schools, small businesses, and public services. We balance our demographics. We strengthen our tax base.

Affordable housing is not a charity project.

It is the most reliable economic strategy we have.

It helps keep taxes stable. It lets us reinvest in infrastructure. It gives people a way to stay rooted in their communities. And it gives the next generation a reason to come back.

The numbers are simple. The return is massive. And the opportunity is right in front of us.

We’re locking up more than $200 million every year to support a development model that loses money over time. Not because we have to, but because we’ve built the rules around it.

It’s a financial trap.

We keep asking if we can afford more affordable housing. But the truth is, we cannot afford anything else.