By Jason Hoover

If you’ve ever looked around New Castle County and wondered why we are constantly playing catch-up with roads, sewers, and public services, you are not alone. The truth is simple, and also unsettling: Our development model is broken, and it’s slowly bankrupting us.

We are building in a way that looks like progress, but in reality, it is slowly draining our budget and weakening our communities. At the center of this problem is a development model that encourages sprawl, hides the true cost of infrastructure, and leaves taxpayers holding the bag.

Let me explain what is happening using a familiar example.

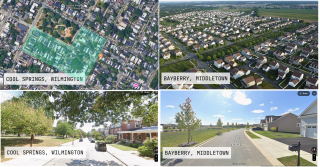

Caption: Sprawling developments stretch as far as the eye can see in Middletown, DE

Imagine a grocery store where the most expensive items are subsidized behind the scenes. Things like imported cheese, filet mignon, and bottles of wine are discounted with public money. Because of that subsidy, these luxury items seem like a good deal at checkout. Over time, the store stops stocking rice, beans, bread, and other essentials. The luxury goods are the only thing left on the shelves.

The store looks full, but most people cannot afford to shop there. Worse yet, the store is no longer serving its original purpose, to provide the basics needed to sustain human life.

We’ve made the most expensive kind of development (large-lot single-family homes, far from services and jobs) the easiest thing to build. And we’ve done it by quietly covering the real costs with public dollars.

The price tags of these homes are artificially low because it does not reflect what it takes to support them. Roads, sewer lines, water systems, emergency services, and stormwater infrastructure all have to be extended to reach them. And once they are built, we have to maintain that infrastructure forever.

The real cost is not paid by the developer. It is paid by the public.

Caption: Sewer and road systems alone account for more than 40% of the county’s total operating budget.

Let’s look at the numbers that explain how this problem adds up.

To support a suburban single-family home, the county typically needs to provide about 78 feet of infrastructure per household. That includes everything from the street in front of the house to the utility lines running underground. In a more compact neighborhood, such as rowhomes or small apartment buildings, that number drops to about 8 feet per household.

The cost to maintain public infrastructure is roughly $12.50 per foot per year.

Here is how it plays out:

Now let’s estimate how many households in the county are built in this high-cost, low-density model. A conservative estimate is about 35,000 homes.

So the math looks like this:

That is more than 30 million dollars in public costs that could be avoided or reduced with better land use decisions.

A Look at the County Budget

In FY2026, New Castle County is spending nearly $88 million on public works — almost a quarter of its entire operating budget. These costs are driven heavily by the infrastructure required to support sprawling development, even though property tax revenues have remained flat.

There are roughly the same number of homes in three city blocks of Cool Springs as in the Bayberry aerial. Both house about the same number of families. The difference is the public cost. The Bayberry pattern needs far more street and pipe per household, so it costs the county about 8 to 10 times more to maintain and is likely a net fiscal loss. Cool Springs sits next to jobs, churches, hospitals, and parks within a few minutes’ walk. Bayberry requires a car for nearly every errand, which pushes more trips onto a few arterial roads and concentrates congestion even with a smaller population. Neighborhoods like Cool Springs are about 10 times more fiscally productive per acre than neighborhoods like Bayberry.

We can't blame developers. They build what the system rewards. Right now, the rules favor large-lot, car-dependent subdivisions because those projects are faster and more profitable. The real costs get externalized. The developer sells the homes, but the county is left paying for the roads, the pipes, and the police response times.

This is how we have ended up in a situation where our infrastructure budget is overextended, services are stretched thin, and taxpayers are wondering where their money went. The system is designed to reward the wrong kind of growth.

There is nothing inherently wrong with suburban or rural-style development. Some people want more space, more privacy, and a bigger yard. That’s fine.

The problem is not the existence of sprawl. The problem is that we are subsidizing it heavily, while under-supporting the kinds of development that are financially sustainable.

One of the most expensive consequences of sprawl is stormwater management. More pavement means more runoff, which requires more pipes, more detention basins, and more maintenance. These costs add up quickly and are a major reason the county’s infrastructure budget keeps growing faster than our revenue.

If we simply priced sprawl honestly, meaning developers and buyers covered the true cost of building and maintaining that kind of growth, it would become less attractive by comparison. Right now, it is artificially cheap because taxpayers are covering the difference.

Pair that with incentives to build walkable, affordable, and diverse housing types, and the economic picture starts to shift. Builders would follow the profit signals, and we would begin to see more neighborhoods that cost less to maintain and offer more options for people at different income levels.

This is how we move toward the kind of growth we say we want. Not by banning sprawl, but by stopping the subsidy that makes it the default.

We have the tools to fix this.

We can start by aligning our policies and incentives with the kinds of development that actually pay for themselves. That includes:

If a new project increases the county’s long-term costs, that information should be part of the decision. Right now, we ignore it. As a result, we keep building obligations we cannot afford to maintain.

We are not facing a moral crisis. We are facing an accounting problem.

The math does not work. We are subsidizing sprawl while struggling to fund the basics. But this is not inevitable. If we start aligning our growth with fiscal sustainability, we can reverse the trend.

We can build places that are affordable, walkable, and financially sound. We can stop treating open space as expendable. We can finally make the economics work for everyone, not just a few.

It starts with telling the truth about what things really cost. When we build smarter, we stop going broke.